By: Vladimir A. Alexeev, International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks; John E. Walsh, International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks; Danica J. Loucks, Department of Anthropology, University of California Irvine; Regine Hock, Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks; and Ute Kaden, School of Education, University of Alaska Fairbanks

The International Arctic Research Center (IARC) started organizing NSF-supported summer schools for students and early career scientists in 2003. These summer schools provide students with the current state of knowledge, hands-on training in conducting Arctic research, and the skills necessary to communicate science across disciplines. We gather experts who introduce the cutting-edge science in their research areas through lectures, model-based experimentation, and field excursions. Invited experts guide the students in group projects, aimed to encourage participants to explore the intersections between traditional disciplines. Graduate students and educators benefit from close interaction with experts who are actively involved in ongoing research and fieldwork in their disciplines. An international component of our project provides perspectives and international collaboration which we regard to be key elements of future Arctic research.

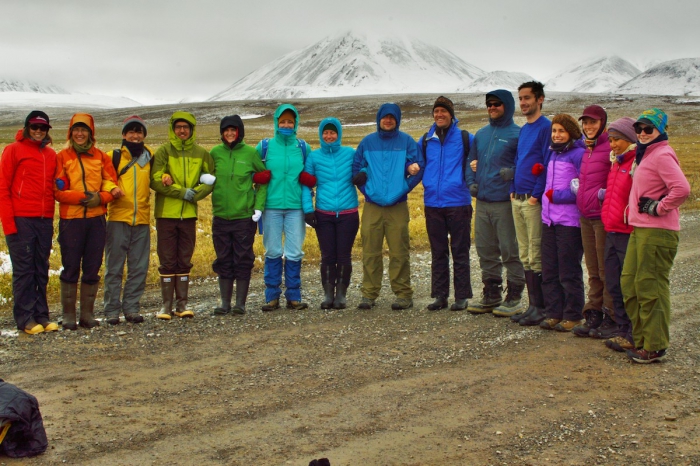

Locations of IARC summer schools have included the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF); Utqiaġvik (previously known as Barrow); Toolik Lake Field Station on the North Slope of Alaska; an Arctic Ocean program conducted jointly with the NSF-funded NABOS Arctic Expedition; King George Island in Antarctica; Kennicott Glacier in Alaska; and other places. Well over 300 students have attended IARC summer schools since 2003. Building on the knowledge gained during these previous summer schools has led to success and innovation in the program.

Lessons Learned from Our Accumulated Experience:

- Diversity among student backgrounds enriches both the scientific and the cultural experience and fosters an international collaborative spirit. Specifically, differing educational and professional backgrounds and varying levels of experience fosters exchanges of knowledge and skills. However, there is likely an optimal difference in relative expertise—if the range of expertise is too large, less experienced participants occasionally feeling “left behind” in collaborative mini-projects, describing that they felt they could observe but not always participate.

- Students should be picked on a strictly competitive basis; only those who are interested and motivated will actively contribute to creating a synergistic atmosphere.

- Students benefit from a small core group of instructors who spend the entire period with the students. Interaction with instructors one-on-one or in small groups is cited by students as some of the most productive learning time. This kind of interaction is integral to helping students learn nuanced approaches of specific analyses, procedures, etc. For instance, in the modeling summer school, the challenging process of learning the more nuanced aspects of working with models, such as how to use good judgment to reduce model uncertainty, appeared to be best learned through talking through problems with instructors or watching instructors walk through a thought process.

- Instructor availability in the summer is hard to predict; therefore, we approach potential candidates four to five months before the summer school begins. We “balance” the list of instructors by inviting scientists from different disciplines. Mini-projects are usually formed around interests of individual instructors.

- Lecturers cover a wide range of topics that expose participants to new research and provided key background information and context for particular kinds of models and processes. One way lectures could be further useful, students reported, would be to include more explicit connections between the information presented and how to build, improve, or use a model.

- Students report that hands-on activities allow them to understand Arctic processes in ways they hadn’t before. Students enthusiastically embrace participating in mini-projects in close interaction with instructors. Project presentations—a highlight of the summer schools—teach useful presentation skills.

- Hosting the summer schools in Arctic locations creates a unique opportunity for students to better understand the physical spaces they are analyzing in their work.

- Informal discussions with instructors and joint work on mini-projects play a big role in forming new collaborations and sometimes grow into long-lasting professional partnerships.

- Pre-event coordination of content, presentations, and projects is essential if a summer program is to be greater than the sum of its parts.

- PhD/postdoctoral students and K-12 audiences have different priorities and require different approaches.

- Science communication is embedded throughout lectures, projects, and discussions of climate models in use. Students expressed a perception that it is important for scientists to engage in science communication in some manner, but many were uncertain about how to do this effectively. Continuing discussions about how research interfaces with users and how that might be communicated could be valuable to students in future summer schools.

IARC is currently continuing the summer school program in collaboration with Tromsø University as a part of the International Partnerships for Excellence in Education and Research (INTPART) project “Arctic Field Summer Schools: Norway-Canada-USA Collaboration”. The project is currently in its second year. The first summer school was conducted in Norway on the R/V Lance and in a classroom setting at Tromsø University. The 2018 summer school will take students to Utqiaġvik (Barrow) and the 2019 school is scheduled to be in Whitehorse, Canada.

Further information about the IARC Summer School program is available on the IARC website.

For questions, contact Vladimir Alexeev (valexeev [at] alaska.edu).

Vladimir Alexeev is a Research Professor at the International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, with expertise in atmospheric science. His research interests are in atmospheric large-scale circulation, permafrost, and the use of a hierarchy of models and observational data to study large-scale dynamics of climate.

Vladimir Alexeev is a Research Professor at the International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, with expertise in atmospheric science. His research interests are in atmospheric large-scale circulation, permafrost, and the use of a hierarchy of models and observational data to study large-scale dynamics of climate.